My Heart

My heart never tires of holding on to the hope of one day becoming everything it longs to be.

When I was a child, I studied at a neighborhood school called Sabor de Mel. The school was painted all yellow, the uniform was yellow, it had a small but tree-filled courtyard where the light poured in. The hallways were always scattered with toys, and there was a little canteen that sold sweets and savory snacks. The students always arrived well-dressed, carrying a colorful backpack and a lunchbox featuring some superhero. We all wore the same uniform, which everyone had to buy at the same store: the same shirt, same shorts, same socks, same sneakers. And I loved the idea of going to school. I was only nine years old and delighted in seeing friends, playing, laughing. A genuine joy arose in me whenever I thought about school.

Until one day, a little classmate called me a monkey.

At first, I didn’t understand, but I felt the malice in her words—and that moment never left my mind. The way she laughed, how she pointed at me, and how the other kids laughed too. And when I later opened a book and saw the picture of a monkey, I realized I was not one—but the saddest part was this: there were no monkeys as students in that school. From then on, I no longer felt like I belonged in that space, and for a long time, I didn’t feel worthy of being there at all.

That wound cut through me and stayed with me throughout my childhood. And though it took me a while to understand that my classmate only wanted to call me ugly, I did feel ugly. But I didn’t feel ugly only at school—I felt ugly in the world.

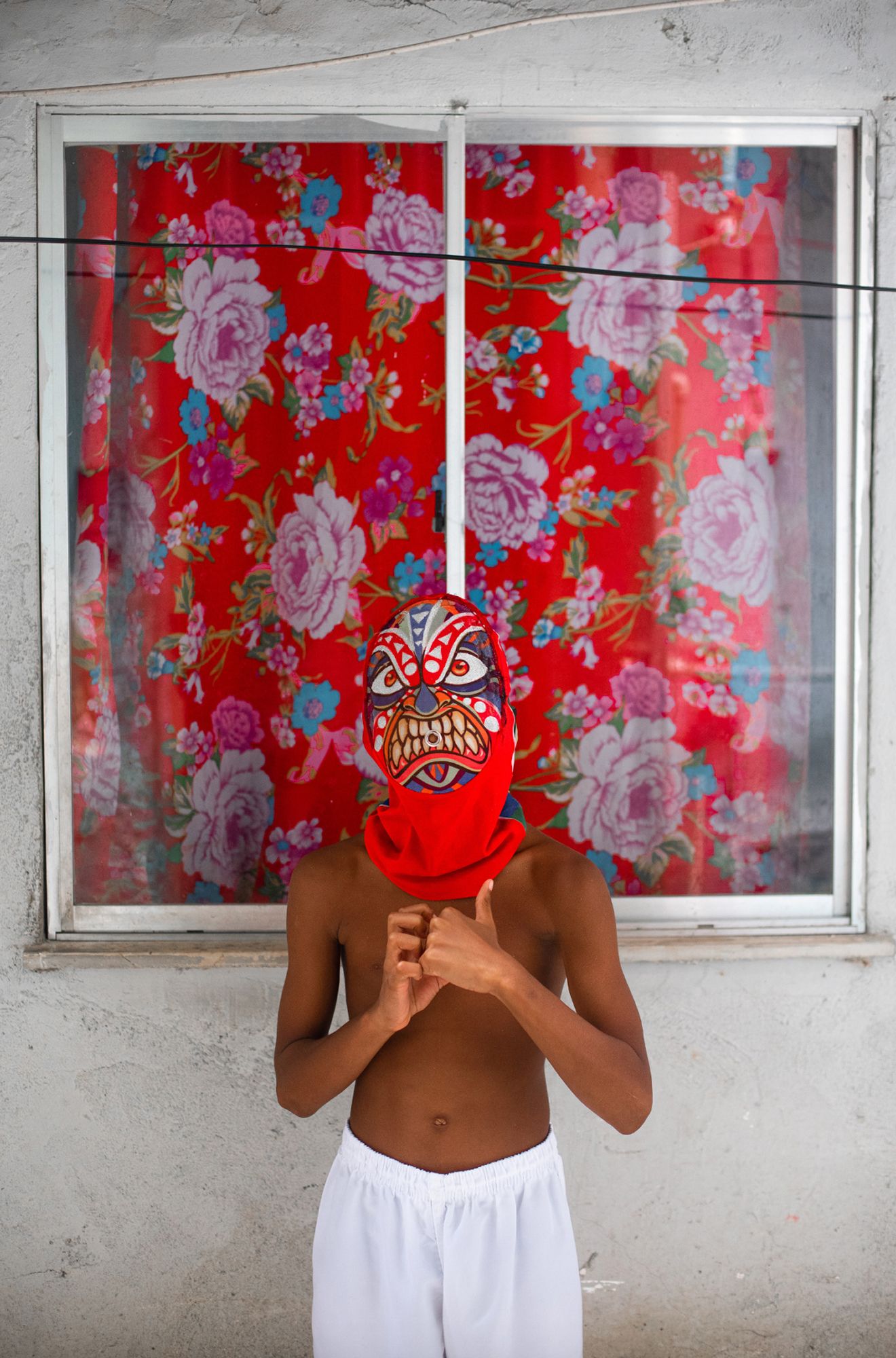

Over time, I learned how to live with that pain, but it kept resurfacing every time I encountered another Black boy on the street, at the beach, at a traffic light, or at the entrance of a restaurant. Unlike other people, I looked them in the eyes. I was drawn to those bodies—young, dark-skinned, with shy smiles and full of scars. Even as a child, I could already see in the gaze of a Black boy a possibility of being and existing in his fullness. And without fully understanding, that dense feeling pushed me toward something I couldn’t yet name.

And one day, staring at myself in the mirror, touching my face, perceiving myself—crying—I realized: those boys are me.

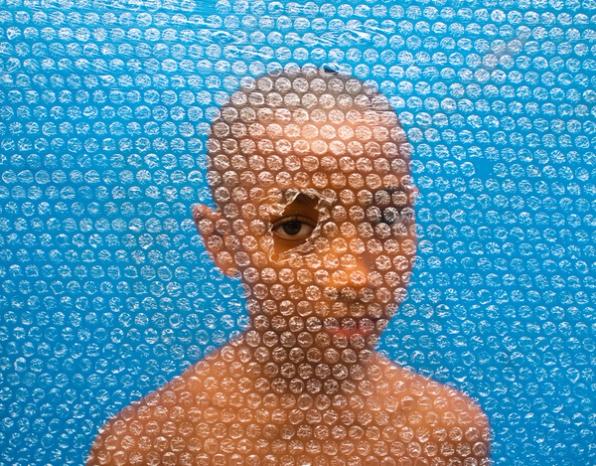

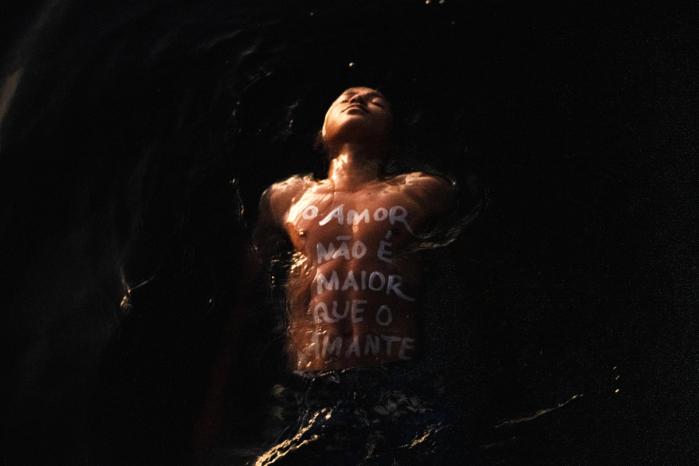

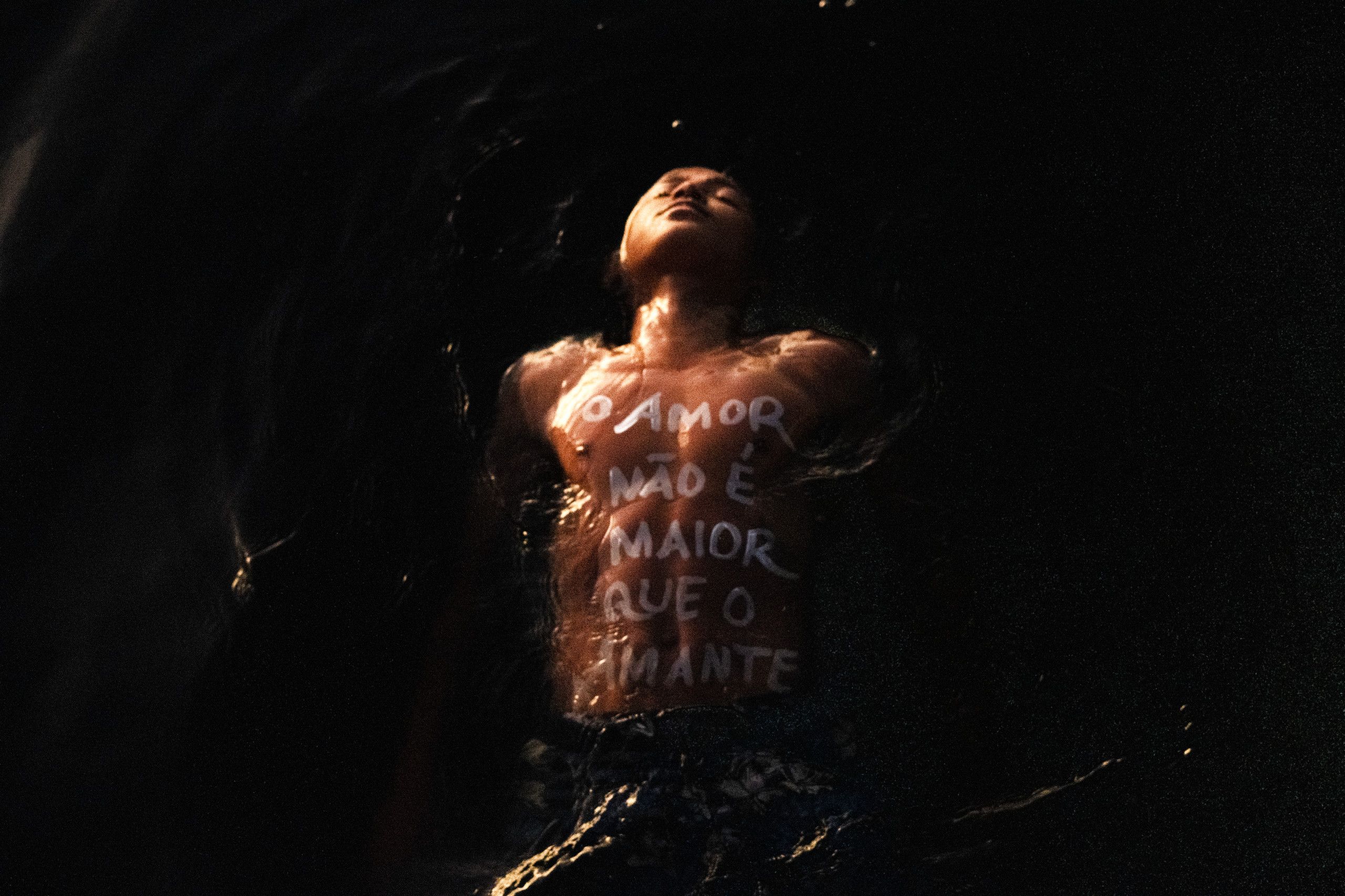

Photography came into my life as a tool people used to eternalize moments, but also to capture beauty. That’s when I decided to use photography as a channel of beauty for those boys. There was an urgency in me to photograph them within a possible narrative of existence—jumping in the ocean, laughing, playing. I just wanted to show the world that I could see them happy.

Over time, the click of my camera began to compete with the click of a gun. My lens began to compete with the lenses of security cameras. And my photographs, hanging on the wall, began to compete with the heavy gaze of prejudice.

In a city surrounded by the sea and by beautiful boys diving, existing, the choice of photography came from the need to carve beauty into the settings, with characters and tools accessible to everyone. It’s about shedding light on erasure. Because even though the camera I shoot with today is lighter, Richard Serra says that everything we choose in life for being light soon reveals its unbearable weight.

And in my heart still lives nine-year-old Wendy, in a yellow uniform, walking to school. I use the creativity of that boy, who still lives in me, to nourish dreams through my imagination. Photography is my impossible real imaginary, which often goes beyond what I can achieve. But I am deeply interested in the journey it allows me to make toward others—so I move closer, and closer still. I cherish the daily effort of looking, of looking again, of confronting my own contradictions so as not to marginalize before I understand the path of a Black boy.

If I am the most beautiful dream of my ancestors, then every Black boy is.

Axé.

Every Boy Is a Sea